A day in January celebrates one man's fight for civil liberties and his defiant stance against what he saw as unjust and discriminatory government orders.

In California and a handful of other states, January 30 is Fred Korematsu Day, which honors the life and legacy of a man who simply refused to have his rights taken away.

With the hostile backdrop of World War II and the U.S. president's order for the mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans, a walk with his girlfriend led to an arrest and touched off a decades-long battle between Korematsu and the country he called his own.

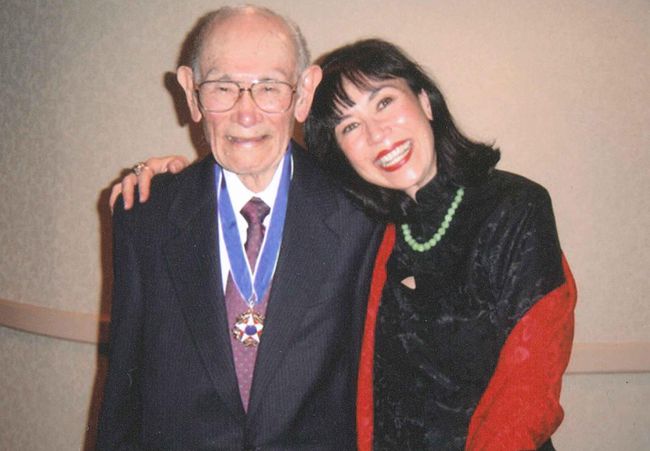

Korematsu's story is about how one man can make a difference, says Karen Korematsu, L.H.D., about her father, who died in 2005 at 86 years old. And in a time when parents and educators are seeking more diverse stories and historical figures to celebrate, Korematsu's story matters now more than ever.

“Children need a positive role model,” says Dr. Korematsu, the founder and executive director of the Fred T. Korematsu Institute. “And to know that in even in the face of adversity, they can make a difference.”

Why Were Japanese Americans Sent to Internment Camps?

For generations of Japanese Americans, Dec. 7, 1941, is the touchstone that formed a community's identity. On the "date which will live in infamy," as President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously called it, Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor killed thousands and launched the United States into war. It is also the date that changed the lives of Japanese Americans.

The attack stirred hysteria and fear that Japanese American friends and neighbors could be spies. The drumbeat of anti-Japanese sentiment—already present in laws that prevented land ownership for many people of color—grew louder.

President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, citing national security as a reason for the mass removal and incarceration of about 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast until the end of WWII.

Officially, the government called them internment camps, but activists today say those are euphemistic terms designed to hide the truth: American citizens were forcibly removed from their homes without due process and incarcerated first at racetracks, then in desolate prison camps surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers.

“The lesson of the wartime treatment of Japanese Americans serves a valuable lesson to future generations about what happens if unconstitutional actions by the nation’s leadership go unchallenged by the public’s silence,” says John Tateishi, a Japanese American and author of Redress: The Inside Story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations.

In 1988, lawmakers passed the Civil Liberties Act and offered an apology and monetary compensation to survivors of the mass incarceration.

“We can never fully right the wrongs of the past,” wrote President George H.W. Bush in the apology letter to survivors. “But we can take a clear stand for justice and recognize that serious injustices were done to Japanese Americans during World War II.”

- RELATED: Parent Guide Helps Asian Families Address Racism During the Pandemic

Who Was Fred Korematsu?

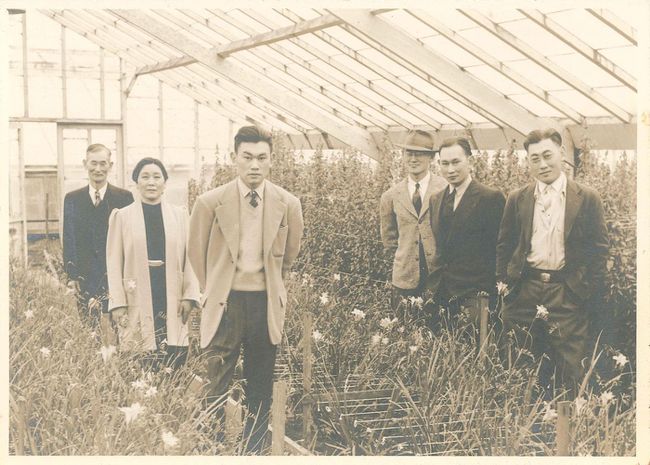

For Korematsu, a second-generation Japanese American, December 7 marked the start of his battle to keep his American-born rights.

In March 1942, when his family was uprooted from their home by military order and incarcerated in government-run prison camps, Korematsu, 23, from Oakland, California, simply refused and stayed back. One day in May 1942, he took a walk, got arrested, and was convicted of resisting a military order. He was later sent to an internment camp.

"I didn't think that the government would go as far as to include American citizens," said Korematsu in the documentary Of Civil Wrongs and Rights.

Instead of accepting the injustice, Korematsu sued the government over the constitutionality of the mass incarceration. The case bore his name, Korematsu v. United States, and was heard by the Supreme Court in 1944, where he lost.

Many years later, it was found that the government had misled the court and the public about the threat posed by Japanese Americans during WWII—they were indeed friends and neighbors who had become collateral in the wartime frenzy.

In 1983, nearly 40 years later, Korematsu entered a courthouse again, this time to be vindicated. His conviction was overturned. "I would like to see the government admit they were wrong," said Korematsu at the hearing. "And do something about it, so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color."

Those closest to Korematsu describe him as a gentle and humble man. His ordinariness led to extraordinary results. Later in life, he crisscrossed the country to speak about civil rights and social justice, using his own story as a cautionary tale. President Bill Clinton awarded Fred Korematsu the Medal of Freedom in 1998.

"His frame and modest personality belied a steely will which anchored his challenges to unfair court decisions," says Dale Minami, one of Korematsu's former attornies.

- RELATED: Anti-Racism for Kids: An Age-by-Age Guide to Fighting Hate

How To Celebrate Korematsu Day With Kids

How do you challenge unjust rules? The Korematsu way is to stand up for yourself without tearing others down.

In 2010, California passed a bill establishing January 30 as Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution. It is the first statewide day named after an Asian American. The day is also celebrated in Hawaii, Virginia, Florida, New York City, and Arizona.

According to his daughter Dr. Korematsu, the family's goal is to urge more states to approve similar legislation on January 30 and eventually advocate for a national holiday.

"I think the most important thing for kids to learn from his life is that one ordinary person can make a change by learning about their rights and standing up for them, for all people in our diverse country," says Peter Irons, a political scientist, and Korematsu's former lawyer.

This January 30, take the time to read more about Korematsu and his story. Laura Atkins and Stan Yogi wrote an exceptional children’s book, Fred Korematsu Speaks Up, with beautiful illustrations and facts that explain the WWII mass incarceration in an age-appropriate way.

The Fred T. Korematsu Institute, a non-profit that advocates for education and racial equity, will host a virtual celebration. Commemorative flags signed by Japanese American WWII incarcerees will be presented in Korematsu’s honor in another virtual event.

Most of all, January 30 is a day to pause and reflect with children on the importance of individual power and dissent.

"Dissent is not the enemy of patriotism," says Minami. "And is sometimes the highest expression of patriotism."

And we need January 30 to remind children—and ourselves—about the basic principles of democracy and justice.