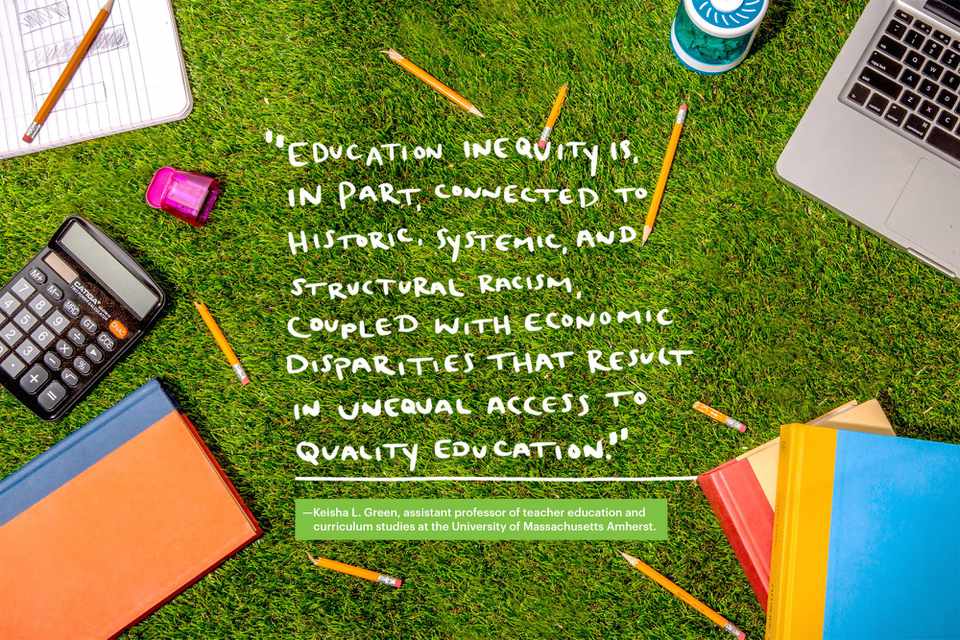

Next year, Keisha L. Green will send her daughter to kindergarten. The University of Massachusetts Amherst associate professor of teacher education and curriculum studies is a big supporter of public education, but she's considering enrolling her daughter in a private school. She's worried that the schools in her community of Springfield, Massachusetts won't give her child an optimal experience.

"I am torn," says Green, who also has an infant son. "I feel like we might be experimenting with our children's educational trajectories by enrolling in public schools."

Green, who is Black, points out that schools in Springfield, a more urban area, spend about $17,000 per pupil, while schools in Amherst, a more suburban community where she works, spend about $23,000 per pupil.

"As a professor in the field of education, my decisions about where to send my children to school are complicated by my idealism for what public schools could be and by what I know to be the realities of public schools, especially for African American and working class families," says Green, who holds a doctorate from Emory University.

Across the United States there's a wide variety in the quality of public schools. Some schools feature the latest technology, several opportunities for students to explore interests in the arts or sports, top-notch facilities, and an extensive list of course offerings, while others struggle to provide the basics. Their buildings may be crumbling. They tend to offer few advanced courses and electives, and they might not have tablets or computers to distribute to students. These disparities were exacerbated by the pandemic.

Child Trends, a research organization based in Maryland, tracks data related to children living in poverty. It found that in 2020 the number of kids living in poverty increased. During the pandemic, child poverty grew nearly two percentage points. That translates to about 12.5 million children living in poverty in the U.S. In 2019, 1.2 million fewer children were living below the poverty line. Black and brown children were hit the hardest. Among Latinx children the poverty rate jumped from 23 percent to 27 percent. It went from 26 percent to 29 percent among Black children.

When many schools went to distance learning during the pandemic, wealthier school districts provided the means for students to keep up, while in many cases, students at schools without a lot of resources floundered. At the end of 2020, the consulting group McKinsey & Company released a report that found that, on average, students of color started the 2020-2021 school year about three to five months behind in math. Their white counterparts were about one to three months behind. McKinsey found that in the fall of 2020 Black and Hispanic students were more likely to still be learning remotely, though “less likely to have access to the prerequisites of learning—devices, internet access, and live contact with teachers.”

The fear is that COVID is causing the opportunity gap to grow, which refers to the disparity in standardized test scores and other education outcomes between white students and Black and Latinx students.

Making school funding more equitable is seen as a viable way to close that gap. Academic research has shown that when kids from low-income families attend well-funded schools they're more likely to graduate high school and less likely to live in poverty as adults.

Researchers in this area tend to focus on equity rather than equality. That's due to the fact that schools that serve students from low-income families need more funding rather than equal funding with wealthier districts to provide resources that will lead to similar outcomes.

Read More:

3 White House Policies That Aim to Close the Education Equity Gap

Schools Must Adjust to Post-Pandemic Student Needs—These Programs Could Help

![An image of grass with school supplies in it with a handwritten quote that reads: “[It comes down] to access and wealth and privilege and how those shake down on color lines, Gretchen Walker a mom in Philadelphia."](https://www.alivay.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/20221004082932-633beeece6a05.jpg)

Scott, who holds a doctorate in education leadership from Harvard, says doing research and asking questions is a great place to start. He suggests parents ask about the demographics of their child's school and about how various groups are faring academically. If they notice disparities, they should speak out to effect change. He suggests the understand-question-advocacy model.

"That is fundamentally what parents do for their kids," says Scott. "Families who are privileged, they seek to understand what's happening for their kids. If they don't like it, they question, and if they don't get the answer, then they advocate for certain things. If more parents did that basic thing for children who didn't look like their children, we'd get a lot further in equity across the country."

Some experts suggest these parents may want to direct their advocacy beyond their child's school, district, or even state. It may take a federal response to achieve true equity in school funding.

Behind the Spotlight

EDITORIAL

Digital Content Director: Julia Dennison; Executive Editor, Trends & Features: Melissa Bykofsky; Executive Editor, Black Parenting: Kelly Glass; Features Editor: Anna Halkidis; SEO Editor: Nicole Harris

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION

Visual Editor: Jillian Sellers; Senior Art Director: Julia Bohan-Upadhyay; Designer: Kailey Whitman; Production Associate: Francesca Spatola

Photography: Aaron DuRall

SOCIAL MEDIA

Senior Manager, Social Strategy: Melissa Chavez; Social Media Coordinator: Leyla Rosario; Social Media Producer, Instagram: Hannah Chambley Williams